Exam 1 scores are now posted on Canvas! Remember that I added one point to everyone’s score (see this post for explanation). Nice job everyone!!

Exam scores will be up soon! One question was bad.

Really great job, everyone! The mean score was 94%!

There was one question that only half of the class answered correctly. That piece of information, together with some other stats, told me that the question tested a concept that I did not clearly explain in class.

Here’s the question:

Q. Which of the following best describes the morphology of cardiac muscle cells?

A. Spindle-shaped, unbranched, non-striated cells

B. Long, unbranched cells with multiple peripheral nuclei

C. Short, branched, striated cells

D. Spindle-shaped, branched, striated cells

E. Long, branched, striated cells

The correct answer is C.

So to compensate, I am adding one point to everyone’s score. That way, the people who answered incorrectly get that point back, and the people who answered correctly are not losing anything. The other way to do it is to just remove the question, but I like this way better.

I will redo the scores and then post everything on Canvas, most likely tomorrow.

Hyaluronic acid products!

In our connective tissue lecture, we talked about hyaluronic acid, this incredibly huge glycosaminoglycan. I mentioned I’d look up a couple things: its molecular weight (over a million daltons – wow!), and the amount of water it holds (hyaluronic acid holds up to 1000 times its weight in water!).

We talked about how it’s used in dermal fillers like Restylane and Juvederm, as well as in topical products that you can buy over the counter.

I didn’t get into this, but I just wanted to mention something about topical hyaluronic acid products, since they’re super common and it’s kinda important to understand a little about how they work.

Older formulations of topical hyaluronic acid had just plain old huge hyaluronic acid (HA) molecules in them, so the HA just sat on top of the skin and – at most – did a little moisturizing. But now, most good HA products contain several different sizes of hyaluronic acid molecules (some even have HA packed into nanoparticles), so they can actually permeate the skin and add some resiliency. Nice!

You guys are young and beautiful already – so you don’t need a lot of extra, expensive products! But topical HA gives you a really nice, moisturized, glowy appearance. In fact, last year after I gave this lecture, several students talked to me about their use of topical HA products and how they swear by them.

So I thought I’d share some information on topical hyaluronic acid products here in case you’re interested.

First, here’s a great overview article on topical hyaluronic acid products from a website I love called Into the Gloss, As an aside, this website was created by Emily Weiss, who founded the blockbuster beauty and skin care brand Glossier. Love, love, love their products!

Here are some high-quality but reasonably-priced topical HA products. These all have multiple sizes of HA so you can be sure you’re getting absorbable HA:

Questions about cilia

Q.I just had a quick question with regards to cilia configuration. On the slide it states that cilia insert into basal bodies with 9 triplets of microtubules. Does that mean 3 axoneme are bundled into a unit and a cilia contains 9 of those units (so a total of 27 axoneme in one cilia)?

A. The arrangement of microtubules at the insertion point into the basal body is a confusing (and mysterious) feature of cilia. So you’re right on in trying to make some sense out of it!

No – the axonemes aren’t bundled in threes – there is just one axoneme (with its characteristic 9 + 2 arrangement of microtubules) per cilium. But you’re right about the insertion point: each cilium inserts into its basal body with an arrangement of microtubules consisting of 9 triplets (and no central pair).

Just exactly how the 9 + 2 arrangement of microtubules in the axoneme changes to the 9 triplet arrangement at the basal body is unclear – there isn’t a consensus on how the transformation happens. So you’re right to wonder about it! Unfortunately, there isn’t a good answer – but at least now you know you’re not missing something important.

Q. In lecture we talked about apical structures such as microvilli and cilia. It says that cilia are inserted into basal bodies, what are those? They aren’t part of the basal lamina even though it has the word basal correct? I am a bit confused because they are apical structures.

A. Great question! The term basal means “bottom” – and we throw it around a lot! In “basal bodies” basal refers to the bottom of the cilium! So basal bodies are little structures at the bottom (base) of each cilium. Basal bodies are the places where axonemes (the central structures of cilia) start growing; they also serve as anchoring structures for the completed axonemes. So yes: the basal bodies are apical structures, and they are not part of the basal lamina.

Q. Why are the 2 central microtubules not a pair but the 9 pairs on the outside are considered pairs (instead of 18 microtubules) in the cilia? Is that because they are of a different type?

A. Thank you for bringing this up! It is confusing that we call this a “9+2” arrangement when it looks like there are 9 pairs of microtubules around the outside, and one pair of microtubules in the middle! Seems like it should be either “9+1” or “18+2.” There’s a good explanation, though. Here’s a diagram of an axoneme – we’ll talk about the “2” part and the “9” part separately below.

The “2” part of the axoneme

The two microtubules in the center of the axoneme are totally separate from each other. So they can be considered to be 2 separate, independent units.

The “9” part of the axoneme

The 18 microtubules around the outside are bound together, two at a time – so they can be thought of as 9 separate, independent units.

It turns out that in each of these 9 units, one of the microtubules is incomplete. If you look at the microtubules circled in red, you can kind of see that the top one looks round, and the bottom one looks like it’s not quite round, and has sort of just latched on to the top one. The bottom one is actually not a fully-formed microtubule (if you pulled the two apart, the top one would be round, and the bottom one would look like a C-shaped structure). So we really shouldn’t even call these guys “pairs” since they don’t consist of two fully-formed microtubules. The official name is “doublet” – and that is a little better than “pair,” I guess.

Question about identifying epithelial cells in tissue specimens

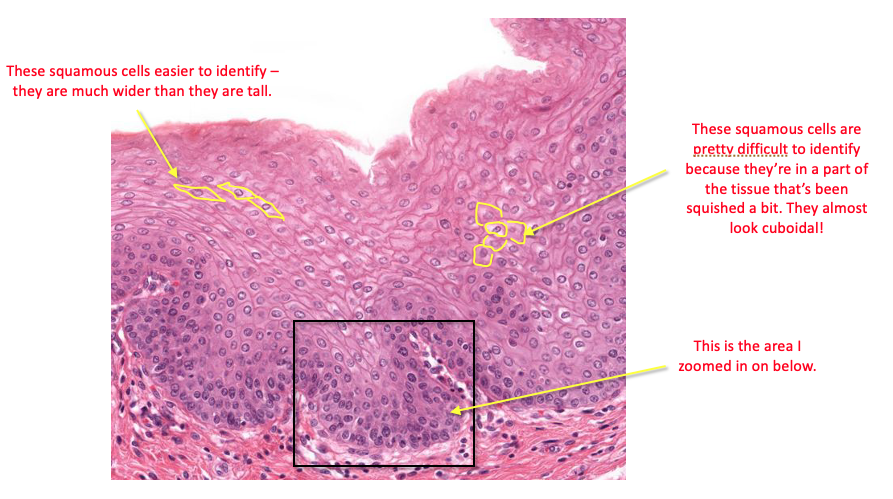

Q. Some of the cells in the stratified squamous epithelium on slide 53 look thicker and almost cuboidal while cells of stratified cuboidal epithelium on slide 54 are almost squished like squamous (especially around the folds in the lining), making them hard for me to distinguish them if I were to be asked without context of where they’re from. What is the typical process in distinguishing the epithelium type of real tissue specimens?

A. I totally get that! It can be really hard when you’re looking at these specimens for the first time; I remember feeling like I could tell what was what if it was pointed out to me – but if I had a slide without arrows, I felt lost.

I think that telling these types of epithelium apart – like many of the new things you’ll be looking at in this course – just becomes easier over time. We’ll see lots of examples of epithelia in all the different organ systems we go through – and you’ll soon get the hang of identifying different types of epithelium (squamous vs. columnar vs. cuboidal; simple vs. stratified), and pretty soon you won’t even have to think about it 🙂

I won’t be showing you pictures on the exam – so you don’t need to worry about being able to identify structures in actual images. I may ask you what a squamous cell looks like – but a lot of my exam questions are related more to the functions of structures (e.g., what is the function of the zonula occludens and how is the zonula adherens different?) I’ve posted some sample exam questions, so take a look at those to see how I tend to write my questions.

Back to your questions on the images – I made some notations to show you how I would know that the cells are squamous vs. cuboidal. Here is slide 53 with some comments:

Questions about glands

Here are some great questions about glandular cells!

Q. I wanted to clear up some confusion I have about glands and glandular cells types. I understand that there are 3 different glands; merocrine, holocrine, and apocrine. Within these glands with specific processes of secretion, there are different kinds of glandular epithelial cells; ion-transporting, serous secretory, mucous secretory, neuroendocrine, and myoepithelial cells. Is this correct?

A. Not quite! You’re correct in saying that based on their method of secretion, there are three types of exocrine glands (merocrine, holocrine, and apocrine). And you’re also correct that there are different types of glandular cells (ion-transporting, serous secretory, etc.).

However, not every gland can be classified as merocrine/holocrine/apocrine! In fact, that’s just one way of looking at/classifying glands – there are actually three different classification schemes, and they overlap with each other sometimes! So it can be kind of confusing at first.

So let’s look at the three ways glands are classified, and then we’ll talk through some examples. Here are the three ways you can classify glands:

1. By the presence or absence of ducts

- Exocrine glands (have ducts)

- Endocrine glands (do not have ducts)

2. In exocrine glands, by the method of secretion

- Merocrine glands (secrete using exocytosis)

- Apocrine glands (a portion of the cell is lost during secretion)

- Holocrine glands (the entire cell is lost during secretion)

3. In exocrine glands, by the nature of the secreted substance

- Serous glands (secrete a thin, watery substance)

- Mucous glands (secrete a thick, viscous substance)

- Mixed serous and mucous glands (secrete both substances)

Sometimes we use all three classification systems when describing a particular gland – but sometimes we just use one or two of them, and leave out the others. For example, some exocrine glands have both merocrine cells and apocrine cells – which means they can’t really be labeled as either merocrine or apocrine.

So you’ll notice when we start talking about glands in different organ systems that we just classify them according to which of the three systems makes the most sense. In the pancreas, for example, we use the labels “exocrine” and “endocrine,” and for the exocrine glands, we also use the labels “serous” and “mucous” – but we don’t use the merocrine/apocrine/holocrine labels.

So the bottom line is that for now, all you need to do is understand the three classification systems above so that when you encounter these descriptions in the future, you’ll know what they mean. But don’t worry about fitting all three classification systems together, because they are used independently of each other.

Q. Can multiple kinds of these cell types exist within a specific gland? For example, can neuroendocrine and mucous secretory cells compose the same apocrine gland?

A. Yes! You can have neuroendocrine cells and mucous secretory cells in the same exocrine gland.

However, as mentioned above, note that these cell types may have different secretion methods (e.g., the neuroendocrine cell may use merocrine secretion, and the mucous secretory cell may use apocrine secretion). If this is the case, then you wouldn’t label the gland “apocrine” – you’d just not use any of the merocrine/holocrine/apocrine labels.

Q. Does the specific glandular cell “take on” the mode of secretion of the gland it composes? For example, would a neuroendocrine cell of a merocrine gland exocytosis its product at the apical end of the cell?

A. Great question! The short answer is no 🙂 If you had a gland composed mostly of cells using merocrine secretion, but it also had some cells using apocrine secretion, those apocrine-secreting cells would not “take on” the merocrine secretion method! They’d just continue to use their preferred apocrine method – and you wouldn’t be able to slap a merocrine, apocrine, or holocrine label on that gland 🙂

The mode of secretion of a gland is determined by the type of cells that are in that gland. So if a gland is made up of cells that use merocrine secretion, it’s called a merocrine gland. If the cells use holocrine secretion, you’d call it a holocrine gland.

Q. Do myoepithelial cells technically secrete any kind of product?

A. No – they typically don’t secrete anything. They’re located around the perimeter of the gland, “hugging” the glandular cells, and their job is to contract and help the glandular cells secrete their products.

Information about Exam 1

This post contains specifics and logistics for our first exam in General Histology (DDS 6214).

Start and end time

The exam is scheduled for Thursday, August 28, and you may take it any time between 12:01 am and 11:59 pm that day. Once you open the exam you have two hours to complete the exam. All submissions must be uploaded by 11:59 pm on Thursday in order to receive a grade.

Accommodations

If you have accommodations for exams, please send me a quick email reminder (if you haven’t already) just so I’m sure I have a complete and accurate list.

Password

The password for the exam is statefair2025.

Classroom availability

Our classroom will be open and available from 1:00 – 3:00 pm on Thursday, if you want to take the exam at that time in our classroom. I’d suggest that if there are several people in the the room, please try to space yourself out well so there’s no way anyone can suggest the possibility of you looking at someone else’s computer 🙂 You can, of course, take the exam anywhere you want – so take it wherever you’re most comfortable.

Content

I aim for roughly 5 questions per lecture hour on our exams (in this class and in our future classes). For this exam, the Intro to Histology lecture was quite short, so I only have two questions on that lecture. Here’s the full breakdown by lecture:

Intro to Histology: 2 questions

Embryology: 5 questions

Epithelial Tissue: 10 questions

Muscle Tissue: 10 questions

Nervous Tissue: 5 questions

Connective Tissue: 6 questions

Cartilage and Bone: 9 questions

All questions are multiple choice with one correct answer, and each question is worth one point.

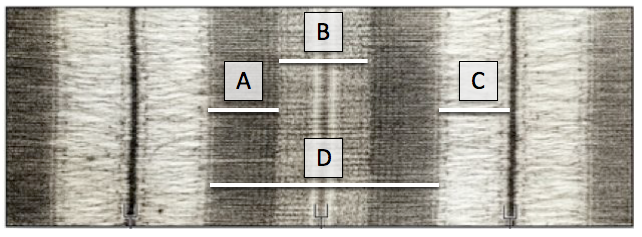

Please take a look at the Sample Exam Questions post to get an idea of how I write questions. There will not be any tissue microscopic images on the exam, but as I mentioned in class, there will be an electron micrograph image of the sarcomere on the exam. Questions 16 and 17 in the Exam 1 Review Kahoot, and question 4 in the Sample Exam Questions post show this image and give you an idea of the kinds of questions I might ask on the exam.

Examplify Information

You will take this exam using Examplify installed on your PC/Macintosh laptop or desktop computer. If Examplify is currently installed, it may require an update and computer restart before the exam. If it is not installed, you should download and install the most up-to-date version of Examplify before the exam.

No scratch paper is allowed during the exam – but I have enabled the digital notepad feature within Examplify, so you can use that if that helps. Also, just a reminder that using electronic devices (phones, tablets, smart watches, headphones) is not allowed while taking the exam.

Also: this is not an open-book, open-note exam – and I trust that you will adhere to the honor code and not use any outside references.

Grading

After you take the exam, you will immediately receive your raw score. Final scores will be posted to your Canvas after I’ve reviewed the exam metrics.

Finally…

If you have any questions please feel free to email me any time.

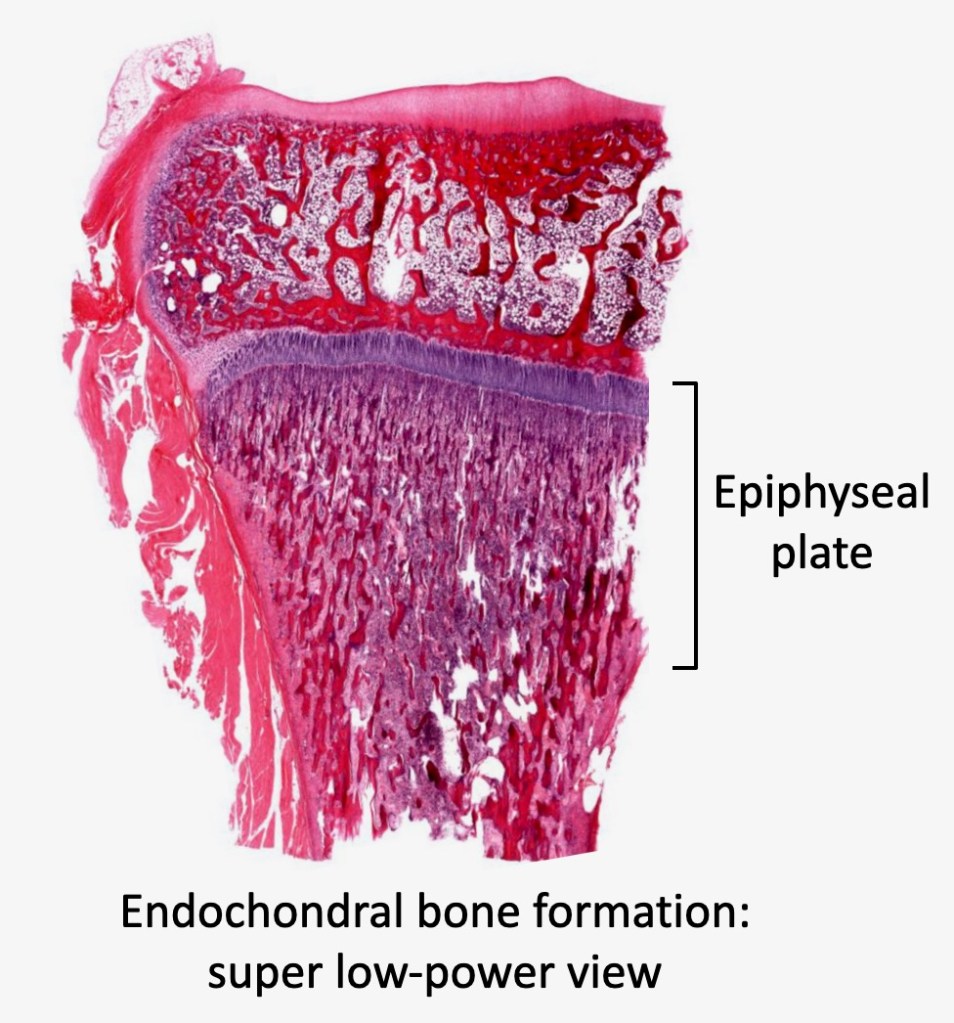

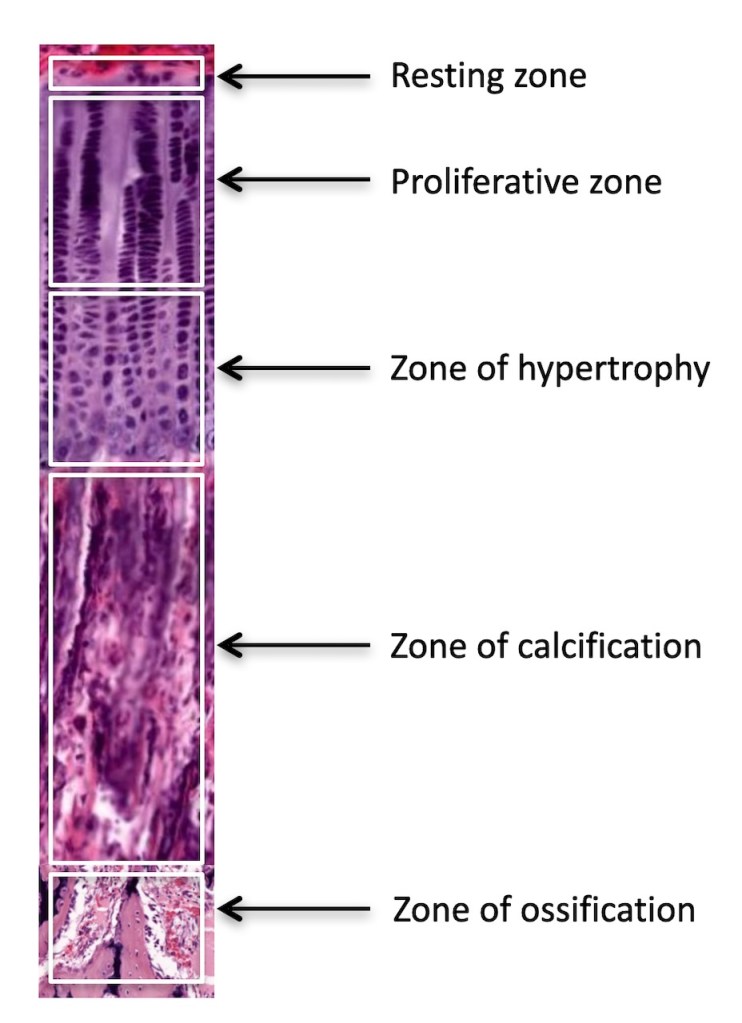

Composite image of layers of the epiphyseal plate

I mentioned in class that I’d put together an image showing all the layers of the epiphyseal plate with labels. Here it is!

First, here’s slide 57 of the Cartilage and Bone lecture, but with a bracket showing you roughly where the epiphyseal plate is located. I say roughly because the zone of calcification blends in so gradually with the zone of ossification that it’s hard to say exactly where the bottom of the plate is. But this will give you at least a rough idea:

And here’s a closeup showing you the different layers, put together in a single composite photo. The original photo didn’t include the zone of ossification, so I added it in at the bottom. So the diagram isn’t exactly proportional – but at least it gives you something to look at so that you can visualize where the layers are from top to bottom.

Why we need 8 hours of sleep a night

Today in our Nervous Tissue lecture, we’re going to talk about the amazing way the brain cleans itself during sleep using what is now known as the glymphatic system.

I wanted to share a bit more here about why getting enough sleep is so very important for your health. This post is all optional reading. However, I’d strongly urge you to glance through this post and see if anything catches your eye.

Sleep is SO important to our health.

But WHY? What happens if you don’t get enough sleep (other than you feel like crap)?

Researchers have shown that when we don’t get enough sleep (meaning, less than 7 hours per night):

- All-cause mortality goes up significantly

- The incidence of cancer increases significantly (see the WHO declaration below!)

- Learning, memory processing, and the long-term storage of new information are all significantly impaired. So you can study like crazy, but if you don’t get enough sleep, you won’t reap the benefits of all that work.

Here are some really good resources I think you’ll find eye-opening (if not a little scary!).

1. Here’s a short Ted talk that describes exactly how the glymphatic system works.

2. The book “Why We Sleep” by Matthew Walker is THE best book I’ve read about sleep.

- Matthew Walker is one of the worlds leading sleep researchers and also a really personable and nice guy (according to a friend of mine who knows him professionally).

- This guy really knows his stuff, and he presents lots of new information about sleep and why it is so critical to our health.

- The audiobook is really good (it is read by the author, who is a great narrator).

3. Here’s a Joe Rogan interview with Matthew Walker:

- Here are the podcast notes if you’re interested but don’t want to watch the whole thing.

- As he does in his book, Matthew talks here about some pretty mind-blowing facts that are way beyond the usual stuff we hear all the time.

- For example, the The World Health Organization has classified shift work as a probable carcinogen, based on the overwhelming research evidence that insufficient sleep is linked to significantly increased risk of certain types of cancer (colon, prostate, and breast). Yikes.

4. Here’s a short video by Matthew Walker that summarizes many of bad things that happen if you don’t get enough sleep.

Sample exam questions

I’d like to give you a heads up on the way I write exam questions, so you’re better prepared for this first exam.

Exam questions should test your knowledge (obviously). You shouldn’t get a question wrong because it was confusing, or because it intentionally led you down the wrong path. When I write questions, I try to be as straightforward and clear as possible, so you understand what the question is asking you. And I don’t try to trick you into picking the wrong answer.

So if you look at a question and you know the answer right away, that’s okay! Don’t worry that you missed some sort of trick, or that the question can’t possibly be that simple.

Here are some examples of typical exam questions (the last two are on lectures we haven’t covered yet, but you can come back here after we do those lectures if you want):

1. In general, what happens during the second phase of the embryonic period?

A. Cells proliferate and migrate

B. Internal and external structures begin to differentiate

C. Organs grow and mature

D. Organs reach their maximum size

2. Which type of intercellular junction attaches epithelial cells to the basal lamina?

A. Zonula occludens (tight junction)

B. Zonula adherens (belt desmosome)

C. Macula adherens (spot desmosome)

D. Gap junction

E. Hemidesmosome

3. What would you call epithelium composed of one layer of cells that are much taller than they are wide?

A. Simple squamous

B. Simple columnar

C. Stratified squamous

D. Stratified cuboidal

E. Pseudostratified columnar

.

Question 4 refers to the electron micrograph above, which shows a sarcomere in its relaxed state.

4. Which letter (and corresponding line) marks a region that contains ONLY myosin filaments?

A. A

B. B

C. C

D. D

5. On H & E staining, which type of connective tissue proper is composed of abundant ground substance, scattered cells, and a few scattered thin fibers?

A. Dense irregular connective tissue

B. Dense regular connective tissue

C. Loose areolar connective tissue

D. Loose reticular connective tissue

6. Which glial cell myelinates axons in the central nervous system?

A. Astrocyte

B. Ependymal cell

C. Microglial cell

D. Oligodendrocyte

E. Schwann cell

.

Scroll down for the answers!

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Answers:

1. B

2. E

3. B

4. B

5. C

6. D